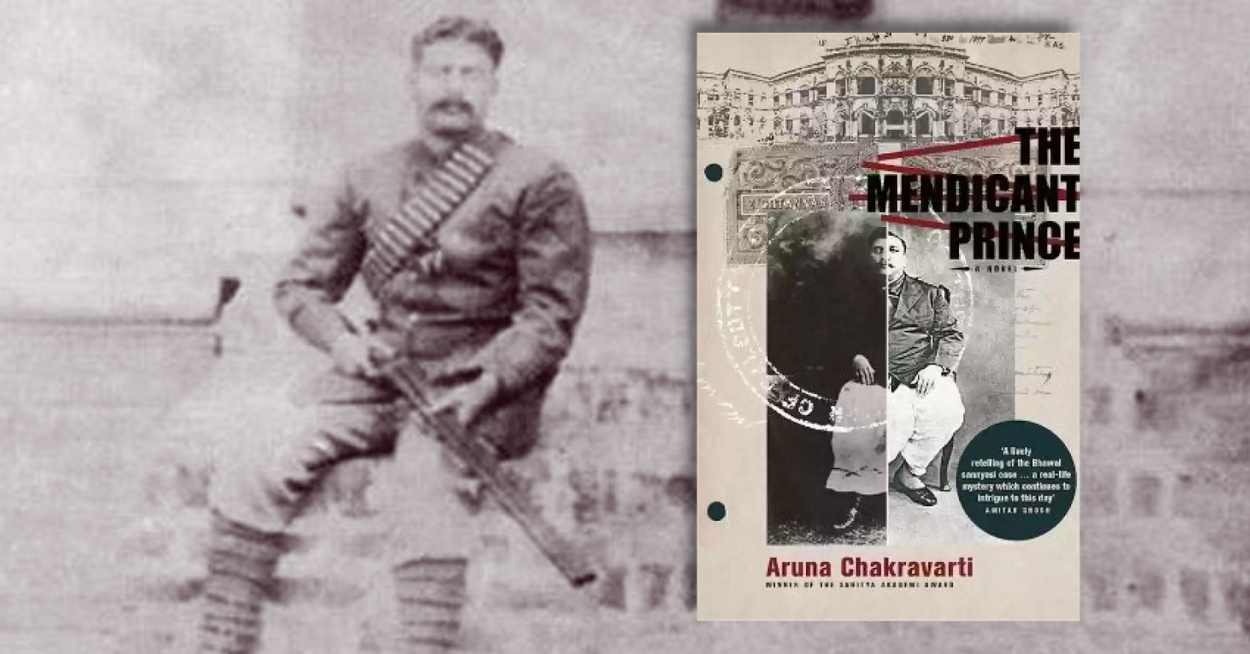

Aruna Chakravarti’s ‘The Mendicant Prince’ is none other than the retelling of the Bhawal Sanyasi case. Taking up an instance from the colonial era, Chakravarty brings forward an adaptation recounting the tragic death of Kumar Ramendranarayan Roy and the rumours that ensued when twelve years after his suspicious cremation, a dreadlocked Naga Sadhu came back to Bhawal, claiming to be the Kumar himself with unquestionable proofs.

The Mejo Kumar of Bhawal, Ramendranarayan Roy was the second among three kumars, who were born to the royal family of the Bhawal estate, a zamindari in “the eastern part of undivided Bengal”. Contracting Syphilis, he later went to Darjeeling on doctor Mahim Dasgupta’s advice, accompanied by his wife Bibhavati Devi and brother-in-law Satyendranath Banerjee, but was reported to have died on 7th May as a result of Gallstones.

While discontentment had already developed with the gossip from servants, about his suspicious cremation and improper funerary rites, it manifested itself in a full-fledged legal battle twelve years later following the return of the Sanyasi and the beginning of a court case filed by Bibhavati devi, his first wife.

Chakravarti’s book is different and unique in the sense that it retells a historical event in a fashion that prompts the reader to ask how this retelling may be different then the ones we will be able to find through digital resources information. Here it is important to look at the fact that the event has been adapted into a novel, a book. Thus, Chakravarti chose to recount and she attempts to recount history through tales of those who in the actual, earlier unfolding of the events were not offered any rights of discursivity.

As a result, what is most captivating is the form of her writing. She wrote a text in the form of perspectives and chose to vocalize those that haven’t been offered the auspicious occasion of being heard. In other words, she chooses the women who primarily maintained the Bhawal estate.

Feminist critique Elaine Showalter coined the term – Female Phase (1921- ) where women writers strived to look within themselves and towards themselves in order to develop a separatist space of writing, rejecting both imitation of man’s literary tendencies and protest against them.

‘The Mendicant Prince’ with its textual theme along the same lines, describes almost every essential news associated with the event through the eyes of the ladies who lived in Bhawal estate. One might ask how it is important. This kind of retelling across spatial and temporal difference of cultures is of value because it explains and offers cues to visual abilities regarding how the oppressors in a patriarchal system of a particular time established rules for the oppressed. This can be understood through the narratorial skills reflected in writing.

Chakravarty offers us a perspective to the sumptuous lifestyle of the raja maharajas of that time. All three kumars of Bhawal indulged in diverse luxuries and the second kumar had a habit of keeping mistresses. Theres was a life lived with truly lavishing luxuries. On the other hand, it also points out the various ways in which their wives were confined within the royal customs.

Highlighting the andarmahal’s atmosphere through the playful banters, fondness with dolls and discussions revolving across appetite of both “royal” and “non-royal” nature, Chakravarty attempts to demarcate the limits of women in the royal house. These were in fact narrower than common woman. Such are also the silent complains of Bibhavati and Anandakumari, the mejo rani and the choto rani respectively.

Thus, while ‘The Mendicant Prince’ is truly a fascinating literary revival of an incident that rocked the entire population of Bhawal, retelling in a sense of rereading can provide a better understanding of the patriarchal ties that not only makes the reader aware of the restraint on women but hints that these very restrictions may have been the result of what happened to mejo kumar, as has been stipulated by the outcome of the legal battle.

Ramendranarayan Roy’s first wife Bibhavati Devi and her brother Satyendranath Banerjee are important to our speculations in this retelling. The mejo rani (Bibhavati) herself admitted the loving yet coercive relationship that she had with her brother.

Dada’s love for me is fierce and possessive…it took forms which thrilled and excited me at the same time. He treated me like an expensive doll, which had to be preserved in a glass case, to be cherished and lavished with care. (p57-58)

His increasing surveillance over her sister’s life and manipulative attitude later helped him in convincing the kumar into applying for an insurance scheme. While women definitely did not have enough liberty to speak during that time, Bibhavati is relatively more silent and unassertive towards her and husband’s life thus giving her brother the space to meddle into it.

The sanyasi also offered an account that convinced the public of Satya Babu’s suspicious behaviour, claiming that he “fell victim to a conspiracy hatched by his brother-in-law Satyendranath Banerjee, an unemployed graduate who wanted to control his share of the estate through his childless sister.” (wikipedia).

‘The Mendicant Prince’ is thus a truly fascinating narrative to read, not only because of the history that it recounts with the richness of the period, but also due to the fact that its rhetoric and especially the manner in which Chakravarty chooses to recount is pedagogical in discussing history through its sociological undertones.

A reading of this book in my opinion is thus important in contemporary times where the past is being manipulated and repainted out of any minority discourse into a retelling that would rather appeal to majority. Attempts of retelling, as that of Chakravarty’s can be a beacon of hope towards a better and improved archive of historical recounting.

The book has been published by Pan Macmillan.