In a poignant autobiographical essay, the lens of filmmaker Mahdi Fleifel zooms in on the Ain-al-hilweh refugee camp in Lebanon. Earning around 30 awards, this emotionally resonant firsthand account with editor Michael Aaglund constructs a multi-layered portrayal of the Palestinian refugees through the lens of a single family’s journey.

Interestingly, the film is set against a backdrop of soulful jazz melodies and nostalgic local songs, strikingly depicting the past and the present. Throughout the documentary, humour emerges as a vital component in preserving the community’s resilience within Ain-al-Hilweh, softening the underlying frustration as these displaced individuals contemplate a ‘return’ to a homeland most of them have never known.

“When I was making the film, I came across a quote by David Ben-Gurion, Israel’s first Prime Minister, who famously said about the dispossessed Palestinians that, one day ‘The old will die and the young will forget.’ Making this film for me has been a way of challenging that. My film is about memory and the need to remember,” reflects Fleifel. “Forgetting for us Palestinians would simply mean ceasing to exist. Our fight throughout history, and still today, is to remain visible. Making this film is a way of reinforcing and strengthening our collective memory. But most importantly, it was a way to record my own family history.”

At a time when we continue to witness the mass extermination of Palestinians, the question of the displaced refugees, who make a plea for their recognition, becomes important. It becomes essential to acknowledge their agencies as humans on earth, worthy of dignity and liberation, even before their heart-wrenching visuals could invoke our sense of humanity. It becomes crucial to extend our empathy by reimagining lives from an eternal craving for belongingness. The film attempts to illuminate the futility of holding onto a piece of land that is no longer one’s home.

Chronicles of Ain-Al-Hilweh: Amidst Strife, Joy and Resilience

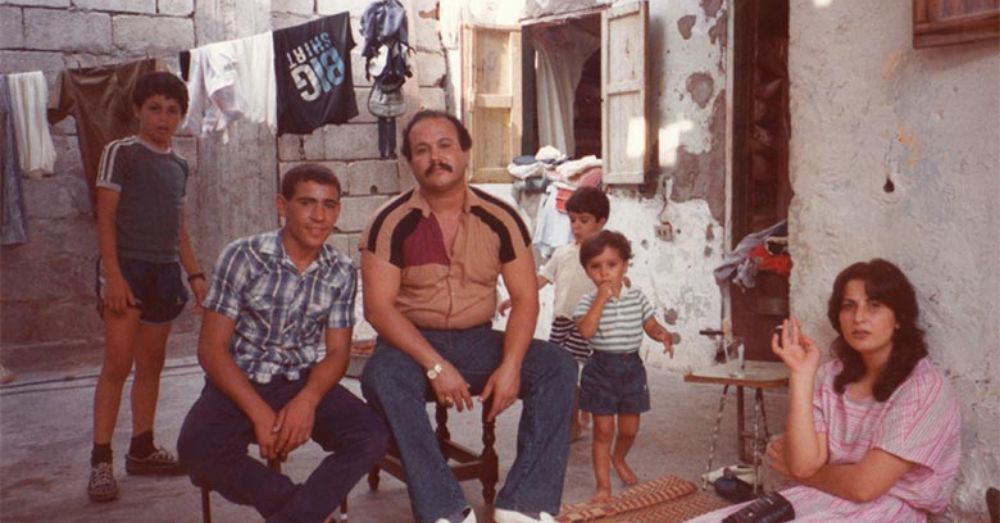

Set between the 1980s and the 2000s, the movie features archival news footage and videos taken over time by Fleifel and his father. The centre stage of the plot is a one-square-kilometre-long Palestinian refugee camp named Ain-al-hilweh ( roughly translated to Sweet Spring ) in Lebanon.

Established in 1948, the camp houses more than 70,000 people, witnessing vertical expansion and accompanying congestion each passing year. Its inhabitants face restrictions on employment in Lebanon, leading to a scarcity of job opportunities and financial resources. The region is marked by persistent political turmoil, frequent episodes of violence, and ongoing tensions with Lebanese security forces, who are barred from entering the camp’s boundaries.

Amidst the turbulent times, Mahdi Fleifel, our storyteller, attempts to portray the tyranny that falls on the crowd of Ain-al-hilweh with their resilience and optimism. His lens gives us glimpses of joyful birthday celebrations where children smile and heartwarming family reunions occur. Festive gatherings occur every four years to mark and revel in the World Cup. Within Ain al-Hilweh, refugees savour everyday pleasures like sipping sodas and owning televisions watching shows like Days of Our Lives and American Idol.

Daily rituals encompass chit-chats over coffee and cigarettes. During his formative years, Fleifel would join his uncle Said to watch American action movies. One scene depicts the departure of a bride, donning a beautiful white wedding dress, leading to jubilant dancing and emotional celebrations for her journey into another part of the world, which would necessarily be better.

While his extended family has continued their existence in Lebanon for over six decades, Fleifel’s immediate family chose a different path of emigration. Raised in Dubai and Denmark, he straddles the dual identities of being both an insider and an outsider in Lebanon. While he has never called Ain-al-hilweh home, Fleifel consistently chose to be in the camp throughout his life. While, on the other hand, for his friend Abu Eyad, it was never a choice but a god-sealed destiny.

He is fueled by a deep-seated resentment of the Palestinians’ second-class status in the state of Lebanon with ‘no rights ‘. To rightly put in his own words, “No future, no work, no education, no nothing!”. With deep ties to the militant organisation Fatah, Abu Eyad serves as Fleifel’s gateway to corners of the camp, rarely accessible to outsiders. He emerges as a compelling and vibrant personality alongside Fleifel’s spirited grandfather and his high-voltage uncle Said.

Abu Eyad narrates his torturous experiences of being caught as a child by security forces for his Fatah connections and how he dreams of making it to another part of the world. He felt their own leaders betrayed them before anybody else could save them from their situation. Abu Eyad, in the later part of the film, is seen to have made it to Greece but, unfortunately, like many others, gets deported back to Ain-al-Hilweh soon.

A Glimpse into the Lives Left Unseen

The movie begins at the security checkpoint of the camp entrance, instantly persuading the viewers to acknowledge their privileges to exist in a world without justifications. There, you meet humans smoking, watching movies and playing football, which helps one escape into a buffer zone. One of the residents shares, ‘Time doesn’t interest me,’ rightfully explaining their abstention from wearing a watch.

In fact, in Ain-al-Hilweh, the passage of years is not measured by clocks but by the quadrennial excitement of the World Cup, where these individuals, existing in a state of de facto statelessness, enthusiastically embrace foreign football teams as their own. In a land where identity papers are mandatory, their collective marginalisation has created a culture rich in narrative and a heartwarming sense of unity.

Fleifel candidly reveals that during his Danish upbringing, he felt embarrassed about his family, striving so hard to fit in. His father’s ways were constant reminders of their ‘otherness.’ There were instances when his father would play loud Arabic music in his parked car in the street and bring out their repressed native spirit. Perhaps, even when they left Ain-al-hilweh, some of Ain-al-Hilweh never chose to leave them.

Films like “A World Not Ours,” which resurrect personal archives in a therapeutic and theatrical revelation, tend to shine when the filmmaker opts for subtlety rather than the clarity of hindsight to shape their narrative. This approach was effectively employed in works like Gastón Solnicki’s “Papirosen” and to some degree in Jonathan Caouette’s “Tarnation”, which incorporates narrative explanations through title cards.

‘A World Not Ours’, borrowing its title from activist Ghassan Kanafanis’ novel, transcends political boundaries, making it an essential viewing for anyone interested in exploring the themes of displacement, family, and privilege. However, the movie has limitations in being unable to voice the concerns of people not within his camera frame. This would specifically include the lives of women and children.

One cannot stop but wonder about the lives of women who get married off to people settled abroad in hopes of a promised bright future, or the women who are stuck in the space with a family to bear, the stories of children who lose out quite early in their childhood and the elders who still haven’t overcome the trauma of Nakba in their teens and the countless other men who smoke hard with a frozen heart to pass a day.

Perhaps Fleifels’ movie gives a window into this regard of oppression. It’s a window that opens into the world of a semi-permanent Palestinian refugee camp in southern Lebanon. Through these glimpses, one critically questions one’s social position and builds the quest to know more. We gain little insight into the experiences of those stranded in a foreign country, their family and their community who hold on to faith, regardless of what it is or is not in store for them in life.