In times like today, when the lines between the State and the Temple have, practically, vanished, Charu Nivedita’s ‘Conversations with Aurangzeb’ (translated by Nandini Krishnan) exposes us to the dying embers of another religious attempt at state-making. It brings the last major Mughal Emperor into public light and does so in an elegant and hilariously satirical way. The writer and the translator’s efforts towards creating such an accessible piece of historical literature deserve much attention, especially with a character whose legacy has been distorted to suit the ongoing Hindutva project.

Nandini, on the first page of the book’s Translator Note, quotes a recent tweet by Hanif Kureishi: “Art should not be safe or complacent; it should frighten, alarm and make us want to throw the book across the room.” About ten pages down the line, the book’s author talks about how his ‘daily activities’ act as easy ‘fodder for the tabloids’, and by this point, it becomes pretty evident that that initial promise will be delivered quite effectively. And, deliver, it does!

From Bhakti in politics to India’s tryst with religion, to art, literature, pornography, and the legacy of the Mughal Empire, this novel ties a neat knotless thread through a range of topics – some contemporary, others timeless, but all of profound philosophical relevance today.

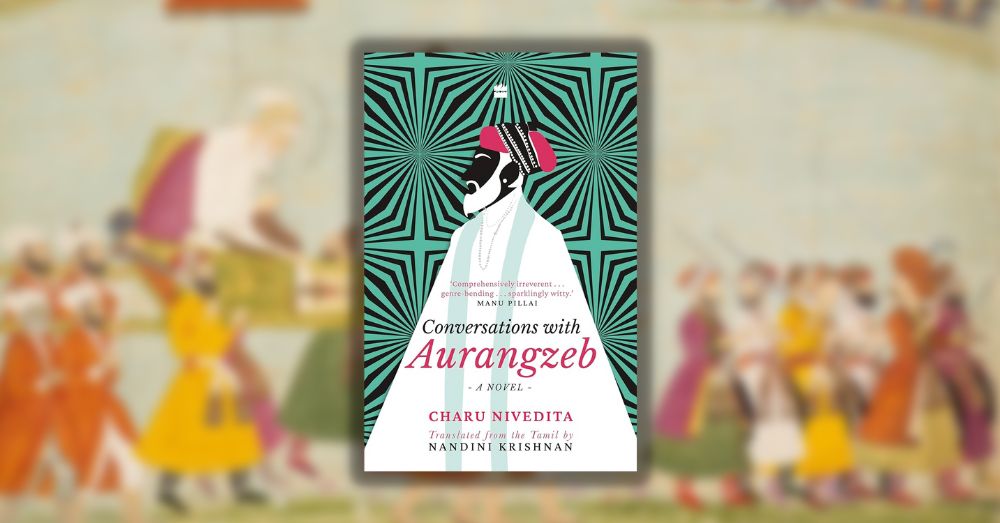

When I was not nodding at or laughing in response to the writer’s words, as Charu chooses to call himself in the book, I was busy underlining and scribbling detailed notes in the blank spaces across the book’s early pages and its edges. To be fair, I picked the book because its title, cover, and plot were a clear sell. But thanks to its topical diversity, its self-awareness, and its to-the-point phrasing, ‘Conversations with Aurangzeb’ is exactly what a self-described history nerd like myself should have expected to enjoy!

Walking the Line Between Fiction and Non-fiction

Reading Manu Pillai’s comment referring to the book as ‘genre-bending’, I had expected it to resemble the typical structure of political fiction. ‘Conversations with Aurangzeb‘, however, is an example of a much more generous form of genre-bending, and Charu’s talent lies in not just blurring but demolishing the walls that separate these genres.

Despite being a straightforward lesson in the workings of the Mughal Empire, and, more specifically, Aurangzeb, the book also delves into themes of supernatural fiction, auto fiction, political analyses, and the like. Moreover, with the gamut of characters that it springs up on us, I could, quite easily, see it take the form of a play, too. But more on that later.

To be clear, this point is not a criticism at all; instead, I see it as a rather integral reason behind the novel’s gripping flow. In fact, both the writer and the translator are keenly aware of this genre-defying trait, with the book referring to it in many different ways. For instance, in ‘Prologue 0’ (the book has six prologues), we are introduced to the writer’s shift from autofiction – the genre he is known for – to history writing.

In ‘Prologue 1’, this focus on history is introduced but quickly abandoned for one of the book’s first plot twists. As the writer’s conversations with Aurangzeb’s spirit are further revealed, we become more accustomed to seeing it as a very informative non-fiction read before we are blindsided, again, by the entry of a seemingly supernatural, and arguably, the funniest, character in the book.

It is in this way that Charu and Nandini keep the readers on their toes, a trait that only a few other history writers, whom I have read, possess. Although the book is officially labelled as fiction, I find more comfort in not limiting it to a certain bracket. Combined with the way it relies on a flexible ‘fourth wall’, it is this amalgamation of genres and ideas that makes the novel so entertaining for me.

Leveraging Humour to Bridge Political Gaps

In recent years, I have found myself to be quite interested in the concept of comedy and humour. In addition to consuming sitcom reruns, skits, and plays, this has also meant that I often try to read material that focuses on its philosophy and politics. So when ‘Conversations with Aurangzeb’ uses humour so freely and deftly, I should highlight that it chooses to do so not just to keep the readers engaged. But the book also uses humour to release a very palpable tension that is inherent to writing about a topic like this.

Aurangzeb, a ruler who is one of the most reviled from India’s princely era, is not an easy person to cover. Not merely because of his misappropriation by the Hindu right, which has converted him into a demon armed by their insecurities. But also because, as one of the last significant Mughal Emperors, his life and death are, in many ways, the last years of the Empire itself, which puts an immense amount of weight on how his story is told.

I believe this is what keeps a lot of us, even on the progressive side, engaging with his life and legacy, often finding comfort in viewing him as just an exception to the Mughal ‘norm’ of secularism. Unlike Baburnama or Akbarnama, both of which I have, at least, heard of, the findings of F. Bernier or N. Manucci was only introduced to me by this book.

So, when the novel relies on humour, it makes history interesting, yes. However, the humour also humanises Aurangzeb, or, at least, his spirit. It works as a sharp knife that suddenly puts him in comparison to his contemporaries, his predecessors and his successors. For example, when his spirit makes itself present for the first time, it says the words: “Fie on you all! Stop that bleeding music at once, I command you!”

Instead of following that with a mention of how Aurangzeb was multilingual – something that the book does later – Charu chooses something else. In comparing this 17th-century Mughal ruler to none other than Shashi Tharoor, the book immediately forces us to chuckle and look at him as just another ruler in just another time. With instances like this one abound, I found myself grinning and swallowing whole chapters rapidly, finishing my first read of this year in just six days.

(Re)Telling an Emperor’s Biography

Talking of genres, I can’t skip mentioning that, at the end of the day, Conversations with Aurangzeb is also a biographical attempt at describing the erstwhile Emperor. In this, too, it doesn’t walk a straightforward path but instead relies on a rather unique form of storytelling, thanks to the fluidity in its genres. The example that I gave earlier about the book’s comparison between Aurangzeb and Tharoor is just one such instance of this form of storytelling.

Another such tactic that the book relies on quite liberally is that of calling ‘witnesses’, all from the spirit realm. The most apparent use of this strategy occurs right as the book begins. The writer, in his attempt to talk to Shah Jahan’s spirit, reaches out to an Aghori (a medium), but the late ruler is, as the book tells it, ‘elbowed out by Aurangzeb’, who wishes to share his own story.

Soon after Aurangzeb’s takeover, the Aghori is overcome by the spirit of Rani Durgavati (the Regent Queen of Gondwana), Murad Baksh (Aurangzeb’s brother whom he had drugged and arrested), and Jahanara Begum (Aurangzeb’s Sufi sister whom he put under house arrest). Through these seemingly second-person accounts, the novel nuances our understanding of Aurangzeb while also appearing as a conversation, a dialogue, which is what also lends it its play-like style.

Speaking of biographical accounts, I also see ‘Conversations with Aurangzeb’ as a biographical account of its creators as well, and I don’t mean this only in a poetic sense. Midway through the book, Aurangzeb’s spirit draws a contrast between his actions and those of the Kauravas in the Mahabharata and reaches this conclusion:

“…the point I’m trying to make is that in a country whose gods are not exempt from human folly, why must a human prove himself as flawless as a god in order not to be cast as a villain?”

By using these words, the book, of course, attempts to talk about the unrealistic standards that one might have for an Emperor whose entire life was a montage of fratricides, patricides, plotting, and warring. However, I find the quote to also reflect the author’s and translator’s ‘shared contemptuousness of political correctness’.

Similarly, in his conversations with the Emperor’s spirit, the writer appears clearly appreciative of progressive movements and actions. Be it by reciting Salvador Allende’s last public address or by emotionally vocalising the tension between the individual and the system, which resides at the centre of criminal law; we are not just made aware of the novel’s characters but also who its creators are.

—

To be fair, this is Charu’s only novel that I have read, and my exposure to him as an individual has also been limited by his thoughts in this book and any commentary on ‘Zero Degree’, his last novel (for example, here). Despite that, I am crucially aware of how his work has been labelled repeatedly. ‘Conversations with Aurangzeb’, in its Translator’s Note, also highlights a few of these labels, namely ‘Pornographic’, ‘Misogynist’, and ‘Conviction-less’. Since I am still making up my mind on how the use of these labels is limiting, let me stick to what I can say from this book alone.

History’s role in searching for answers can not be overstated, especially in today’s volatile and conflict-ridden world. In this world, Conversations with Aurangzeb is a must-read, primarily because in guiding us through the late Emperor’s life and lifestyle, it shows us, over and over again, that no Historical Analysis is ever complete.

This is the one lesson that I, as a curious leftist, would like to remember. Because until we realise what we lack, we can only dream of reclaiming the space that we have ceded to those on the right in recent years.

This book has been published by Harper Collins.