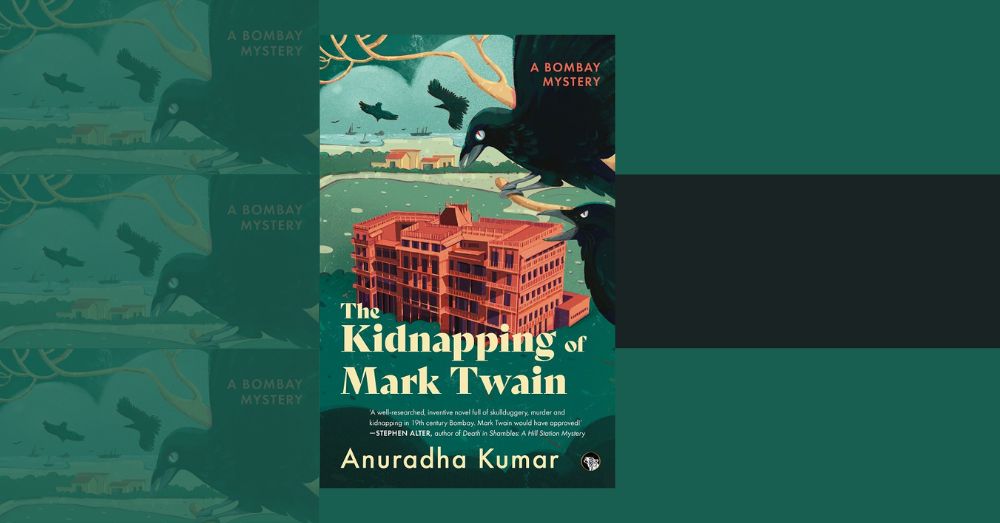

The Kidnapping of Mark Twain by Anuradha Kumar forms part of a coming-of-age detective fiction where its narratives put forth a challenge to the usual contemptuous notions spread against the value of popular literature and the importance of its study among the academic reading lists.

On The Book Itself

Set in January 1896 Bombay Gazette, part fiction and part historical, Anuradha Kumar brings forth celebrated American writer Samuel Langhorne Clemens, popularly known as Mark Twain, and his world round trip with daughter Clara and wife Olivia that began in 1895, following his arrival in Bombay in 1896 to stay at the Watson’s Hotel, to dive into the events of the narrative.

While the pages commence with a passive interaction between Maya Burton, a sort of nowhere person’ looking to merge into the cosmopolitan ways of Bombay and American trade Consul, Henry Baker, looking for ways to impress the former, his romantic interest, the real plot that links the novel to its title doesn’t commence until chapter 5 Small Disappearances that Tell the Real Story. Why then does Kumar plan to dwell on the mention of the murder in the city, the dynamics in Maya’s and Henry’s personal journey as well as the fascinating party at Cowasjee Bengali’s mansion?

A Post-Colonial Reader’s Interpretation

These questions lay in the nature of the story that the author has tried to present to the audience.

Detective fiction at heart, the book also presents a portal for the reader to hop into a series of investigative hermeneutics right at the beginning. Unlike any simple detective formula narrative, Kumar goes back in time, somewhere within the country’s history as a colonial empire of the British Raj. This is in my opinion, one of the most admirable aspects of the book.

As a popular literary genre, detective fiction, like other genres in that category, is perceived as fulfilling the notion of the public demand and thus following the same formula synthesis.

Encyclopaedia Britannica also points at this, stating that a detective novel generally offers ‘(1) the seemingly perfect crime; (2) the wrongly accused suspect at whom circumstantial evidence points; (3) the bungling of dim-witted police; (4) the greater powers of observation and superior mind of the detective; and (5) the startling and unexpected denouement, in which the detective reveals how the identity of the culprit was ascertained.’

However, Anuradha Kumar doesn’t follow this rule.

Not only does she make an effort to trace multiple phases of Bombay under the British in front of post-colonial eyes, but she remains subversive with her plot in the sense that her story diverts from the public demand and instead creates something to which the public itself has to adapt.

Elaborating along those lines, as a fiction along the colonial shadows, she doesn’t focus entirely on the British functioning in the country but also looks at other elements that continue to maintain the city in an orientalist light. There is not only a description of the British police and American and European gaze looking for commercial success within the colony, but the natives as well, convinced to make the rich richer, as the Bengalees’ unhidden expression of disappointment at the absence of Prince of Wales in their mansion during his Bombay visit, comes to light.

Moreover, the guilt of Arthur Pease, a reverend, and his easy accessibility to Opium was a commendable effort at attracting attention towards the reality of faces creating religious propaganda. To be concise in explanation, it is not only the chapters on disappearance, attack, and Twain’s recovery that deserve all the attention. As a passionate reader, one needs to ask questions as to why Kumar chose this particular trajectory.

Hers is a writing that, in my opinion, has carved a niche among writers like Janice Hallett, who have been successful in transforming perspective towards popular fiction and emphasizing the opinion that popular literature is worth studying as part of the academic world.

An Entertaining Plot

While captivating to my literary and academic mind, the narrative proved to be equally exemplary as it wove a genuine tapestry of 19th-century Bombay and the political narrative of the period. A perfect read for Mumbaikars, the novel can entice its audience to wander around Mumbai as a flaneur would, taking in the mystery hidden in the corridors of the Watson’s Hotel located in the Kala Ghoda area of Mumbai.

More importantly, Maya’s fascinating character and quick thinking continue to balance Henry’s careful approach, making a Mr and Mrs Smith pair of detectives out of them that successfully manage the predicament.

While I would have liked to see more of Abdul and a much clearer and subtle socio-political context around the women workers in the factory, the book made up for a fascinating, unputdownable read that I would recommend to others and it undoubtedly encouraged me to surf through more of Kumar’s work in the Mumbai series.

The book has been published by Speaking Tiger Books. Follow them on YKA here.