The UNFPA (United Nations Fund for Population Activities) defines period poverty as the challenges that women and girls who live in a low-income household face when trying to afford menstrual products.

Furthermore, the UNFPA’s article on period poverty states, “The term also refers to the increased economic vulnerability women and girls face due to the financial burden posed by menstrual supplies. These include not only menstrual pads and tampons, but also related costs such as pain medication and underwear.”

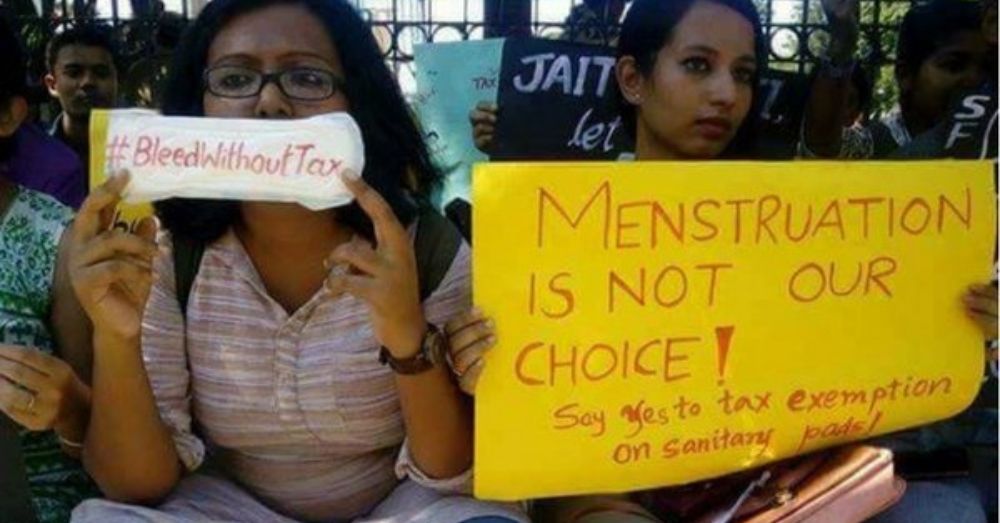

It certainly doesn’t help that menstruation is a taboo in approximately 70-90% of countries, though the amount of shame associated with menstruation differs widely. To say that the implications of these backward views on menstruation are damaging would be an understatement.

In countries such as Ghana, Tanzania, India, Indonesia and Nepal, women are exiled to a hut when menstruating as they are considered impure. The problem arises not just with the problematic premise of this practice but with the conditions of the hut they are expected to live in for three to seven days when menstruating.

In fact, in Nepal, there is a name to this practice. It is known as Chhaupadi. In the Chhaupadi tradition, women and girls are prohibited from touching other people or objects and are banished from community events and various kinds of everyday chores at home.

Women and girls are expelled by the Chhaupadi tradition to live and sleep in menstruation huts or “Chhau huts”, or livestock sheds. These behaviors, which lead to poor menstrual hygiene and negative physical and mental health outcomes, are motivated by detrimental beliefs and practices that are now prevalent in western Nepal.

These huts are often poorly constructed, crumbling structures that aren’t equipped with even the most basic menstrual necessities such as pads or clean, running water. Oftentimes, the huts are so poorly constructed that snakes and other deadly animals (such as scorpions) can enter the hut and cause harm to the woman inside.

Moreover, women are forbidden from exiting the hut for the entire duration of their period which means that they are prohibited from seeking medical help if they do get injured. Some of these injuries could prove to be fatal.

Even without injuries, women residing in these huts are prone to other health issues. It is well known that poor menstrual hygiene can pose physical health risks and has been linked to reproductive and urinary tract infections. Without access to clean, running water and menstrual products, women and girls who are subject to this practice are at great risk every month.

Recent articles claim that the practice is not as widespread in recent years. However, based on the results of the current poll, 84% of teenage females reported practicing Chhaupadi during their most recent menstrual cycle.

Girls between the ages of 15 and 17 who were born into a nuclear family with an illiterate mother were considered to be strong candidates for the Chhaupadi practice. The majority of the girls who practiced Chhaupadi acknowledged limitations in their social and household activities (86%).

Laws, acts, and regulations that were designated as higher-level policy texts featured provisions for financial resources, independent monitoring procedures, and judicial corrective remedies. However, sufficient fiscal commitment and independent monitoring mechanisms were absent from middle-level (policies and plans) and lower-level (directives) documents.

Seeing as period poverty is an extremely prevalent social issue, it is evident that certain measures should be taken to reduce the impact of period poverty on women and little girls all over the world who are at the receiving end of this regressive practices and social stigma.

If you would like to help end the plight of millions of girls world-over, you may consider donating to organizations such as Project Stree and the NOW foundation that are working to end period poverty.