In December of 2022, the BMC ( Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation) received its fair share of criticism. As a part of its ‘beautification project ‘leading up to the G20 meetings, it hung big white curtains in front of several slum areas of the city. Against the government’s literal cover-up of its negligence towards millions of its citizens who lack proper housing, a peculiar phenomenon exists where slums aren’t concealed but exhibited – Slum Tourism.

Slum Tourism, a form of modern tourism, involves tourists venturing into less developed regions to observe poverty and the lives of those entrenched in it. At its best, it’s hailed as ‘life-changing,’ ‘inspiring,’ and ‘educational.’ At its worst, it’s described as ‘voyeuristic,’ ‘exploitative,’ and ‘reeking of privilege.’

To gain insights into the expectations and reactions of tourists embarking on slum tours, one can explore YouTube channels where these experiences are documented. The common thumbnail image features a young, white, English-speaking traveller, often dressed in adventure attire, ready for a “life-altering experience.” Their facial expressions frequently convey a mix of shock and disbelief, as if they can’t fathom life without air conditioning and matcha lattes. In today’s world, travellers often exhibit a been-there, done-that mentality, seeking to explore the unexplored, providing ample opportunities for tour operators worldwide to arrange such unique experiences.

Survival Strategies of the Poor: A Spectacle for the Rich In Dharavi

One of the most frequented destinations for slum tourism happens to be the Dharavi slum, situated in the heart of Mumbai. Its allure reached its peak when it briefly surpassed even the Taj Mahal in popularity among tourists visiting India. Slum Tourism in Dharavi takes an interesting shape. It has moved a step away from just watching people live in squalor but tries to present itself as a celebration of communal self-reliance.

The history of Dharavi, which dates back to the pre-colonial era, has been marked with instances of apathy, unaccountability and carelessness by the authorities. The countless redevelopment plans, which have been massive failures in the past, have prompted architects and urban planners like Charles Corre to comment, “There is very little vision. They’re more like hallucinations.” The “entrepreneurial spirit” and the community solidarity of Dharavi are nothing but a reaction to this long history of disillusionment and a way of taking the matter of their survival into their own hands.

By taking the position of an appreciator rather than a critic of the lifestyle of the residents, travellers elevate themselves from being simple voyeurs to admirers of the ‘work ethic’ of the poor.

While speaking about the strange popularity of Dharavi and the wide reach of public interest it has created, a spokesperson from NGO Dharavi Market told me, “Dharavi is a human experiment. Not just tourists, but architects, urban planners, and sociologists take a keen interest in the working and the functioning of this settlement”

Much has been written about the tourists and the ethics surrounding the concept of slum tourism, but the focus is never on the opinions of the slum inhabitants, who are the subject and the object of this million-dollar industry.

According to a study done in Dharavi (from which the testimonials of Dharavi residents that are written below are taken), four different categories of perspectives about slum tourism can be identified among the residents. Broadly speaking, these are apprehensive, positive, indifferent, and sceptical.

Not surprisingly, most residents hold an indifferent attitude towards slum tourism. They are aware of it but don’t necessarily consider it to be relevant to their lives. This view is further validated by NGO Dharavi Market, “Time is money in Dharavi. Here, people work 12-15 hours a day 6 days a week. As long as there is no disruption in their routine economic activities, they aren’t against tourism.”

Many residents do not perceive slum tourism as a net negative as its expected benefits outweigh the existing disadvantages. Pride in foreign interest, potential opportunities for children’s education, respectful narratives regarding the community and the possibility of instigating change in society are all viewed as benefits.

However, what is interesting and worth noting is that economic growth, such as employment generation, was not mentioned as one of the benefits. “Even if there are some economic benefits, they are limited to a very small minority. The revenue generated by these tourism firms is huge, and the trickling down of profits has limited scope,” an NGO working for youth empowerment and capacity building in Dharavi told me. They also went on to say that the existence of such charitable projects is not very visible in the community, at least not enough to make any big tangible changes.

The aforementioned study further confirms this view. Most residents were unaware of the philanthropic nature of these organisations. Few residents make the connection between the commercial tours and the community work done through them.

Many parents hold the interaction of tourists with their children in a positive light. Although the interactions are limited, they see this as an opportunity for their children to polish their English. “When the children are happy because of the tourists, the parents are happy too,” said a 26-year-old female formerly employed as a caterer in the study mentioned above.

The residents who express apprehension are mostly perplexed by the concept itself. They find it unusual that so many people want to visit their neighbourhood. They question the purpose and intent of such tours. “The first time, I was pretty surprised, but if the same thing is going on over and over, it becomes normal. I actually thought that there might be some problem in their own country, so they came to live here,” expressed a college student living in the area.

Invariably, there are some negative perceptions and complaints as well. There have been concerns regarding the safety of the tourists who visit the little workshops spread all across Dharavi. These industries are not without risk, and the tourists can harm themselves, creating problems for the residents. Grievances about photography are also prevalent. Residents take an issue with misrepresenting the community through the photographic medium.

Some residents are also sceptical that the tourists exploit their bad living conditions for their entertainment. “I thought, ‘Why are they coming here?! What is there to see? They should go to the Gateway of India or some better place to see’. I just thought they came here to make fun of us, of our living conditions here,” objected the owner of an aluminium compound factory.

Can Slum tourism be ethical? Hearing the other side

Slum Tourism glorifies poverty. Replying to this assertion while in a conversation with me, Krishna, the co-founder of Reality Tours and Travels, emphasised the duality of Dharavi. “Our goal is not to romanticise life in the slums. Instead, we wanted to show the other side of slums. We want to dispel the negative perceptions and give something back to the community.” 80% of profits generated by Reality Tours go to their various community service projects like youth empowerment programs, English classes, sports training programs, etc. They were the first organisation to bring the concept of slum tours in India circa 2005

He went on to say that while acknowledging the various challenges of living in a slum, we must also acknowledge the uniqueness of Dharavi as a commercial hub. “Every single inch of Dharavi is utilised. Wherever you go in Dharavi, you can hear the sound of machinery, even at midnight. Isn’t that a positive thing?”

He also commented on employment generation: “We are a socially responsible organisation. We hire youth from marginalised communities as tour guides. We currently have 12-13 tourist guides working for us in Mumbai.” Speaking of other economic benefits, he stated that although generally no remuneration is provided to residents for putting their lives on display, payments are made to families who plan lunches or other festivities for the tourists.

But Slum Tourism in Dharavi is no longer limited to a single organisation. It’s a bustling market that has garnered the attention of many tour agencies ready to jump on the trend. Speaking on this matter, he noted that “Now Dharavi is a 5-star slum. There are so many other companies trying to do what we do. Now, if you walk around Colaba Causeway, you will find people trying to sell slum tours.”

He also expressed concerns about other tour agencies not being strict about ensuring the residents’ privacy. Some allow pictures to be taken and might lack the sensitivity required to conduct these tours.

A net negative or a net positive?

Can slum tourism eradicate poverty? Definitely not. Can it benefit some community members economically? Possibly yes. Is it the best way to engage with impoverished communities? Probably not. Can it dispel some negative stereotypes like laziness and crime associated with poverty? Based on the testimonial of the tourists: Yes, it can. Can the often upbeat and optimistic tone of it lead to the depoliticisation of poverty? Absolutely yes.

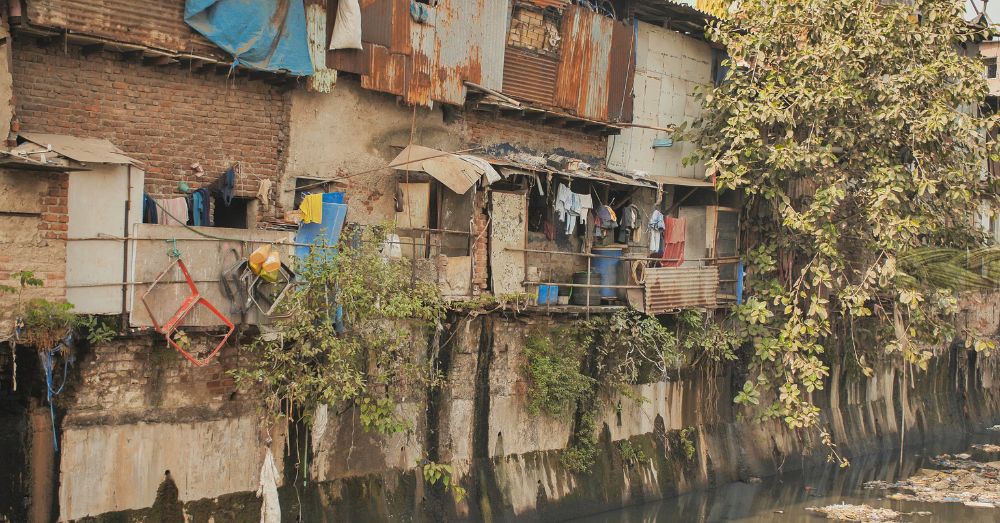

Confronting poverty compels Western tourists to feel anxious about their privilege. One of the ways tourists negotiate this anxiety is by presenting impoverished communities as ‘poor but happy’. Instead of recognising the plethora of issues that exist in Dharavi, like water pollution, dangerous working conditions, open sewage and general lack of sanitation, lack of open spaces for children to play in and so on, they applaud the resilience and resourcefulness of the residents. The problems can get obscured and go unaddressed due to the emphasis on the ‘bright side’.

Slum Tourism is ultimately a polarising topic. The popular opinion among the residents seems to be of acceptance, but this is not to be mistaken for uncritical enthusiasm. Dharavi’s philosophy of ‘live and let live’ echoes this stance. They do not necessarily see it as a vehicle of change but instead as a business venture that might have some positive byproducts.

So, if not slum tourism, then what is a better alternative to support Dharavi? “Long-term engagement with the community is essential to bring about any real change. Superficial interactions are not enough.” opined an NGO that works for youth empowerment in the area.

The word ‘tourism’ invariably refers to some form of recreation, relaxation or pleasure. Keeping this in mind, slum tourism cannot make itself immune to the voyeuristic allegations unless it detaches itself from the word tourism and rebrands itself as a volunteering initiative.

The existence of slums sustains the whole premise of slum tourism.

Unless the tourists are ready to take up the role of activists and are willing to work with the local communities to achieve better living conditions, slum tourism would continue to be analyzed with suspicion.

This story has been written as part of the My City Writers’ Training Program.